There has been a lot of buzz about climate change and the future of wine recently, starting with a New York Times article on Sunday and spreading all around the web. Now there is a video to help us envision the research.

They say that a picture is worth a thousand words, so a cool “fly-over” animation like the one at the top of this post must speak volumes (see this article about the video and the research behind it). As you circle the globe in the video, keep these color codes in mind so that you can interpret the images.

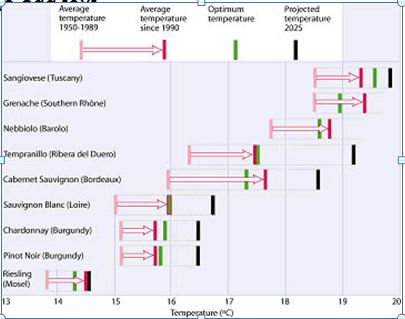

Bear in mind that forecasting is difficult, especially about the future, so projections shouldn’t be confused with fact. But quality wine grapes are sensitive to climate change as this chart from Bemjamin Lewin’s Wine Myths and Realities (see p. 79) makes clear. Relatively small changes in average temperature can have significant impacts on vineyard patterns and, as the video suggests, the impact varies in different regions.

While the dramatic changes you see in the video may not happen, they certain could. And some of the possible climate effects go beyond the sort of changes that might be mitigated by adaptations and innovations in viticultural practices.

Food for thought.

It is scary. Scarier still is all the uncertainty around this topic.

Mike

Relevant article from Down Under!

Michael Hince

Melbourne

Australia

Glass of red could mean more than a hangover

Date April 10, 2013 – 4:00PM

Will Oremus – The Age

In 50 years, wines from Bordeaux and Tuscany will be insipid. Instead, we’ll all be drinking Montana merlots and Chinese clarets.

That, at any rate, is the implication of a paper published online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which estimates that anywhere from 19 to 73 per cent of the land suitable for wine-growing in today’s major wine regions will be lost to climate change by 2050. (The wide variance reflects the great uncertainty in climate prediction models.) As vineyards in Spain, Italy, and southern France wither, colder regions that are inhospitable today will be poised to take their place as the new grands crus.

C’est la vie, right? Climate change giveth, and climate change taketh away.

There’s just one catch, according to the study. Many of those new wine regions coincide with important habitat for species such as the grey wolf, the pronghorn, the grizzly bear, and in China’s case, the panda.

The most promising new region of all, according to lead author Lee Hannah of the non-profit organisation Conservation International, may be the area north of Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming. That would put it directly in the path of a conservation initiative designed to connect Yellowstone to the Yukon. It’s that very type of wildlife corridor that scientists say may be needed to allow animals such as grizzly bears to respond to climate change themselves. “Vineyards would be a major impediment to this connectivity,” Hannah writes in a blog post about the study. “They provide poor habitat for wildlife, and would probably have to be fenced to avoid bears snacking on the grapes.”

We’ve long known that wine grapes are particularly sensitive to climatic shifts. But the idea of vintners and pandas duking it out in a death match in the highlands of China is obviously not an appealing one for any of the parties concerned. Can it be avoided?

One encouraging sign is that vintners are already finding ways to adapt to climate change on the land they own today. As climate change intensifies, they can continue to adapt by uprooting old vines and replacing them with varietals more suited to warm weather, among other adaptations. At the same time, some are already buying new land on higher ground as “climate insurance”. And China is now the world’s fastest growing wine region.

The real key to the sustainable evolution of the wine industry, writes Hannah, will be shifting winemakers’ environmental focus. Today a growing number are raising their grapes organically and biodynamically, which is well and good. But this approach leaves out the larger environmental problems of land use and impact on wildlife. If you’re destroying habitat to build your “sustainable” vineyard and enclosing it with fences, that isn’t really sustainable at all.

To remedy this, Hannah suggests that “consumers make it known that wildlife-friendly wine production is important to them”. Wine producers could respond by following the lead of partnerships such as the Biodiversity and Wine Initiative in the Cape region of South Africa, which plans new vineyards in concert with conservation groups to protect the most sensitive habitats.

Who’s up for a panda-friendly pinot?

Slate

Will Oremus is the lead blogger for Future Tense, reporting on emerging technologies, tech policy and digital culture.

Dramatic video but doubtful of value as it just applies a uniform increase of temperature across the board. All climate is local and the assumption of where “good” wine grapes can do their best is clouded by years of misinformation. In California the maritime influence trumps daily heating, as it does in many parts of the world. For example the Bay area, the southern ends of Napa and Sonoma, the Sacramento Delta and Lodi, Salinas valley, etc will be cooler and more windy as the higher heats in the northern and southern ends of the Central valley will intensify the balancing cold airflow from the Pacific. The real impact will most likely be timing and amounts of rainfall, more warm fall storms and less winter mountain snowfall, which will be challenging but can be addressed.

And total heat over the season, along with season length. As you say, if temperature was all that mattered to grape growing, then there’d be a lot more wine regions in the 30-50 degree latitude belts.