The conventional wisdom is that we are likely entering the first significant period of stagflation — inflation + stagnant economic growth — in several decades. We have experienced recessions in the recent past, but not rising inflation, and not the two of them at once.

The conventional wisdom is that we are likely entering the first significant period of stagflation — inflation + stagnant economic growth — in several decades. We have experienced recessions in the recent past, but not rising inflation, and not the two of them at once.

Inflation is in the headlines every day, but unemployment is very low — so why worry about slow growth or a recession? The answer is that while Federal Reserve policies will try to finesse the situation and bring inflation down to a “soft landing,” most observers think that a sharp contraction will be necessary to bring inflationary expectations down. Growth will fall while inflation still runs high, at least for a while.

So, these are uncharted waters for business and government leaders, especially since it comes on the heels of the covid crisis, which has shaken so many economic and social structures. It is, as I have argued here, uncharted territory for the wine business, too.

So far, as I suggest in last week’s Wine Economist newsletter, wine prices overall have not risen to the degree you might expect given the many cost pressures the industry confronts. Average wine prices seem to have actually fallen in real terms so far according to the data I have surveyed.

It may be premature to begin worrying about how wine consumers will react to higher prices in the stagflation context if and when they arrive. Or — and this is my point — it might be strategic to consider possible scenarios in order to prepare for the eventuality. Because this is uncharted territory — and because, as Jon Fredrikson says, there are no one-liners in wine — it makes sense to consider the range of consumers responses rather than to look for a single silver bullet answer.

Herewith, therefore, a brief and incomplete list of possible consumer responses to rising wine prices in the context of stagflation.

Econ 101: substitution, income, and wealth effects.

We begin with Econ 101 basics. An increase in the relative price of wine would create a substitution effect to some extent. It might be to substitute other beverage alcohol products for wine or — the trading down effect — to substitute less expensive types of wine for previous purchases. How this plays out depends on a number of factors. Younger drinkers, for example, are known to be less loyal to wine and more prone to dividing their purchases among many beverage types, so the substitution effect may be stronger for them than for boomers, for example.

Of these three effects the substitution effect is the most interesting to me because we don’t have much recent experience of supply-driven price increases in wine (versus demand-driven “premiumization”.

The income effect, driven by both higher wine prices and higher prices in general, points towards lower consumption of wine overall. Wine is already more expensive than most beer and spirits on a per-serving basis, and so vulnerable to income-driven consumption adjustments.

There is also likely to be a wealth effect, with wine consumption falling as consumers (mainly but not exclusively boomers) re-assessing buying decisions in light of changing net worth. Rising interest rates implemented to fight the inflation tend to reduce the value of bond holdings directly and equity values indirectly through their impact of the present value of corporate cash flows. Substantial interest rate rises are likely to affect portfolio balances and 401k holdings. If you have been watching the way that equity markets have reacted to the Federal Reserve’s initial 1/2 percent interest rate increase you know what I am talking about.

Stalking the Illusive Wine Bargain

In a perfectly competitive market the “Law of One Price” rules, but the wine market has many quirks and peculiarities, so similar products can sell for very different prices. Rising wine prices are likely to push price-sensitive buyers to even more aggressive bargain hunting efforts. Expect your local Grocery Outlet store to do even more wine business.

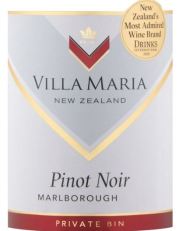

But bargain hunting doesn’t necessarily mean searching for rock bottom prices. We recently received samples of two wines that represent good value in their respective categories. The pitch that came with the wines was that these are inflation-fighters. The first wine was Villa Maria Marlborough Pinot Noir Private Bin, which retails for about $19.00. It is an excellent wine that sells for less that many comparable products from, say, Oregon or France.

The second wine was Le Volte dell’Ornellaia, a “Super-Tuscan” from the Bolgheri region that, at around $29, represents a way for many consumers to raise a glass in high style without breaking the bank. How do you find inflation-fighter wines like these? Start by asking whoever sells you wine to solve a puzzle — I’d like a wine like this, but I want to pay something more like that. A good wine seller will appreciate the challenge.

Risk Management

Buying wine is not easy because it is what economists call an “experience good.” You won’t really know if you will like a particular bottle of wine until you buy it and pour yourself a glass. Reviews and so forth help, of course, but the taste of wine is ultimately very subjective and the risk of disappointment almost inevitable.

As inflation pushes wine prices higher, the disappointment risk becomes more of an issue. One strategy that consumers are likely to adopt in this circumstance is to concentrate their purchases on a few tried-and-true brands or grape varieties that they trust to consistently please. Trying new wines from different regions and brands made from different grape varieties is great fun, but the high reward when you find an exceptionally pleasing wine comes with high risk of disappointment.

So don’t be surprised if consumers — and the stores and shops who sell them wine — react to wine inflation by doubling down on tried-and-true wines. This reinforces a trend that emerged during the pandemic wine surge.

But don’t forget that all this is predicated on wine prices finally rising as fast or faster than the general inflation rates. This hasn’t happened yet … and it might not happen at all. Stay tuned.

Mike, years ago, I had a wine retail store in Arlington, VA during the 2007 recession (I know they say ’08, but believe me when I tell you that that recession started in November 2007; there was no holiday season whatsoever). In any case, the very interesting thing that happened then was the tightening of wine selections by distributors. Prior to the recession, especially in a market like DC, we had unbelievable selection of all types of wines from all over the world, however obscure. If I read about a region, I could find numerous examples that I could feature in a tasting, say, and offer to customers. The recession ended all that. Distributors jettisoned obscure wines and fled to the security of better-known categories. For a small shop like ours that competed on selection, it had a big impact that made the world of wine less interesting. To the extent that selection has expanded again in recent years, I wonder if the same phenomenon will happen. I would assume so.

All very interesting.

Good food for thought as usual Mike.

Couple of builds:

1. Wine Intelligence consumer usage and attitude data also suggests that there is an income effect on consumption. Those on higher incomes tend to have less price elasticity of demand as their disposable income (ie that which is left over after basics have been paid for) is by definition larger, and therefore more flexible.

2. The substitution effect also has an interesting relationship to the individual’s involvement in the category – something we measure very closely, because it tends to dictate behaviour more reliably than demography. What we learned in the pandemic was that highly involved wine consumers (ie those who care about the category) tended to be the ones who traded up during lockdowns so they could replicate a restaurant experience in the home; those who didn’t care so much about wine generally stuck to their normal brands or traded out of the category altogether.