This is The Wine Economist’s 200th post since it began a little more than three years ago under the name “Grape Expectations” — a good opportunity to reflect briefly on readership trends, just as I did when we passed milepost 100.

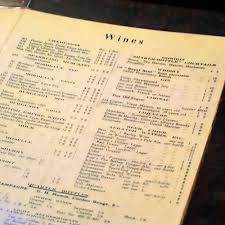

- Not that kind of list!

Milepost 200

The Wine Economist has an unusually broad readership given its focus (wine economics), content (no wine reviews, no ratings) and style (most posts are way longer than is typical for weblogs).

I never expected to get millions of visitors like Dr. Vino or Gary V. and other popular wine critic sites, so I’m surprised by how many people have found this page and come back to read and re-read.

About 200,000 visitors have clicked on these links, sometimes with surprising intensity. The Wine Economist has been ranked as high as #6 in the big “Food” category where wine blogs are filed in Technorati‘s daily ratings and as high as the top 30 in the even broader “Living” group.

Reader Favorites

The most-read articles of the last few days are always listed in the right-hand column on this page, so it is easy to see track reader behavior. I thought you might be interested in readership trends since the blog began. Here are the top ten Wine Economist articles of all time.

- Costco and Global Wine — about America’s #1 wine retailer, Costco.

- Wine’s Future: It’s in the Bag (in the Bag in the Box) — why “box wine” should be taken seriously.

- The World’s Best Wine Magazine? Is it Decanter?

- [Yellow Tail] Tales or how business professors explain Yellow Tail’s success.

- Olive Garden and the Future of American Wine or how Olive Garden came to be #1 in American restaurant wine sales.

- Australia at the Tipping Point — one of many posts about the continuing crisis in Oz.

- No Wine Before Its Time explains the difference between fine wine and a flat-pack antique finish Ikea Aspelund bedside table.

- How will the Economic Crisis affect Wine — one of many posts on wine and the recession. Can you believe that some people said that wine sales would rise?

- Wine Distribution Bottleneck — damned three tier system!

- Curse of the Blue Nun or the rise and fall and rise again of German wine.

As you can see, it is a pretty eclectic mix of topics reflecting, I think, both the quite diverse interests of wine enthusiasts and wine’s inherently complex nature.

My Back Pages

What are my favorite posts? Unsurprisingly, they are columns that connected most directly to people. Wine is a relationship business; building and honoring relationships is what it is all about.

KW’s report on the wine scene in Kabul, Afghanistan has to be near the top of my personal list, for example. I am looking forward to following this friend’s exploits in and out of wine for many years to come. (Afghan authorities found KW’s report so threatening that they blocked access to The Wine Economist in that country!)

Matt Ferchen and Steve Burkhalter (both former students of mine now based in China) reported on Portugal’s efforts to break into the wine market there. The commentaries by Matt, Steve and KW received a lot of attention inside the wine trade, but their thoughtful, fresh approaches also drew links, re-posts and readers from the far corners of the web world.

Looking back, I think my favorite post was probably the very first one, a report on my experiences working with the all-volunteer bottling crew at Fielding Hills winery. I learned a lot that day about the real world of wine and I continue to benefit from my association with Mike and Karen Wade (and their daughter, Robin, another former student) who have taught me a lot about wine, wine making and wine markets.

Look for another report like this when The Wine Economist turns 300. Cheers!

>>><<<

Thanks to everyone who’s helped me in various ways with these first 200 posts. I couldn’t have done it without you! (Special thanks to Sue, my #1 research assistant!)

| Views | ||

|---|---|---|

| Home page | 67,337 | |

| Costco and Global Wine | 6,627 | |

| Wine’s Future: It’s in the Bag (in the B | 6,191 | |

| The World’s Best Wine Magazine? | 5,429 | |

| [Yellow Tail] Tales | 3,921 | |

| Olive Garden and the Future of American | 2,852 | |

| Australia at the Tipping Point | 2,581 | |

| No Wine Before Its Time | 2,483 | |

| How will the Economic Crisis affect Wine | 2,357 | |

| Wine Distribution Bottleneck | 2,185 | |

| Curse of the Blue Nun |

The stock market has the jitters these days and one of the causes is the fear that, even with massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, we may be experiencing a jobless recovery. Things looks OK from the outside (some of the numbers are pretty good), but bad things are still happening deep down where it counts.

The stock market has the jitters these days and one of the causes is the fear that, even with massive fiscal and monetary stimulus, we may be experiencing a jobless recovery. Things looks OK from the outside (some of the numbers are pretty good), but bad things are still happening deep down where it counts.

Our friend Jerry doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would go digging around in the closeout bin or shopping for wine at

Our friend Jerry doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would go digging around in the closeout bin or shopping for wine at

How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery.

How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery. Benjamin Lewin MW,

Benjamin Lewin MW,  The top brands in Bordeaux were established by the Classification of 1855, which grouped the chateaux into a rigid quality hierarchy based upon market prices at that time. This, Dr. Lewin’s analysis suggests, was a bit of a fraud as well, and not a very reliable guide to wine choices today.

The top brands in Bordeaux were established by the Classification of 1855, which grouped the chateaux into a rigid quality hierarchy based upon market prices at that time. This, Dr. Lewin’s analysis suggests, was a bit of a fraud as well, and not a very reliable guide to wine choices today. Decanter.com

Decanter.com