The global wine industry continues to adjust to the “new normal” market environment, with recent news stories focusing on strategies to support demand (Come Over October), grubbing-up programs to reduce grape supply, and restructuring wine winemaking businesses (Vintage Wine Estates bankruptcy, Duckhorn Vineyards acquisition, etc.) after a surge of consolidation fueled by cheap money came to a sudden end.

The restructuring has sometimes returned wineries to the people and families that founded them. In other cases (here I am thinking specifically about Stags Leap Wine Cellars and Col Solare in Washington State) a family-winery partner (the Antinori family) has acquired control from its unintended private-equity co-owner. I hesitate to generalize, but the situation suggests that the advantages of family ownership and control in the wine business are becoming clear again.

I wrote a series of columns about family versus corporate wine regimes back in 2015 and I thought it might be useful to re-publish excerpts from two of them now because the issues they addressed seem relevant again today. Hope you find them interesting.

The Curious Dominance of Family-Owned Wine Businesses in the U.S.

May 5, 2015

Last week’s column about the rise and fall of the Taylor Wine Company of New York raises a number of interesting issues and one of them is the singular importance of family-owned and privately-held businesses in the U.S. wine industry and the very mixed record of publicly-listed wine corporations. In retrospect, a case can be made that Taylor’s downfall began when they made the initial move from family ownership to public corporation.

The conventional wisdom holds that family-owned and privately held firms can be very successful, but their scale and scope are necessarily limited. Corporations, it is said, can have better access to capital and may be able to negotiate risk more successfully because of limited liability structure. You might expect the largest firms in any given industry to be corporations and this is true in some industries, but not in others.

Wine Exceptionalism

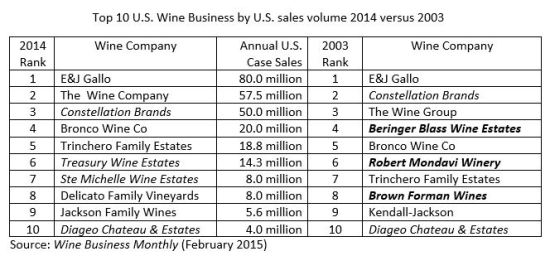

Wine is one exception to the dominant corporation rule. Here (above) is a table of the ten largest wine businesses in the U.S. market (measured by estimated or reported volume not value of sales) for 2014 and 2003. The data are from Wine Business Monthly, which publishes an analysis of the 30 biggest U.S. wine firms each February. I’m looking at just the top ten to keep the analysis simple, although I should note that these ten firms collectively account for about three-quarters of all wine sold in the U.S.

Looking at the 2014 data, you will note that only four of the top ten firms (those in italics) are public corporations or subsidiaries of public corporations. The other six are family-owned or, like The Wine Group, privately-held and together they produce more than half of all the wine sold in America. [editors note: There was a typo in te graph, which should list The Wine Group not The Wine Company.] The bias towards private- and family-ownership is even stronger if we look at the next 20 wineries where only a few corporate names like Pernod Ricard make the list.

Looking closely at the 2014 numbers it is hard not to be impressed by the growth of family firms Delicato and Jackson Family Estates and also the success of Ste Michelle Wine Estates, which seems to behave like a privately-held firm even though it is a subsidiary of a public one, albeit in a different line of business (Altria specializes in tobacco products, not drinks).

All in the Family

Family- and private-owned wine companies are if anything more important today than they were before the Great Recession. Why are family-owned wineries so vibrant despite their structural economic limitations?

The conventional answer to this question — and there is in fact a substantial academic literature dealing with family businesses and even family wine businesses — stresses the ways that family businesses take a multi-generational approach and are able to negotiate the trade-off between short run returns and long run value. Corporations, it is said, are sometimes driven too much by quarterly returns and end up sacrificing the long term to achieve immediate financial goals.

When business requires a long run vision, it is said, families gain an advantage. Wine is certainly a business where it is necessary to look into the future if only because vines are perennials not annuals like corn or soybeans and successful brands are perennials, too.

Another school of thought examines issues of trust and transactions costs within the firm and the ways that family ties can reduce internal barriers and make interactions more effective. It is commonplace to say that wine is a relationship business and family firms may have advantages in this regard. I have knows some family wine businesses that even go out of their way to work with family-owned distributors and so forth. I think one author saw family-to-family links (the Casella family and the Deutsch family) as keys to the success of Yellow Tail brand wine.

Maybe the Real Question Is …

There are good explanations for the success of family-owned wine businesses, but sometimes they feel a bit ad hoc, tailored to explain a particular case and less capable of generalization. And they often fail to fully account for the fact that many family businesses (and family-owned wine businesses) either fail or, like the Taylor family, end going over to the dark corporate side. Family relationships can be good, bad or ugly — you cannot think of the Mondavi family story without channeling an episode of Family Feud) and not every new generation wants to stay in the business. So there must be something more here than simple families think long-term. But maybe we are actually asking the wrong question.

Maybe the question isn’t why family-owned wine businesses are so strong and instead why corporate owned wine businesses are sometimes so ineffective. Is there something about wine that turns smart corporate brains to mush (not all of them, of course, but maybe some of them)? Come back next week for some thoughts on this provocative question.

The Curse of Corporate Wine-Think?

May 12, 2015

Protecting Assets versus Leveraging Them

One difference that I have noticed about family wine businesses versus some of the corporations regards the role of key assets such as brand and reputation. Many family wineries that come to mind seems to see their role as protecting brand and reputation so that they will continue to provide benefits well into the future. Some corporations that come to mind, on the other hand, seem to focus on leveraging brand and reputation in order to increase short run returns.

What’s the problem with leveraging a brand? Leverage has the potential to increase returns in any business, but it also increases risk. And one risk is that the integrity of key assets can be undermined by the leverage process itself.

An example? Well, I hate to pick on Treasury Wine Estates because they have seen enough bad news in the last few years, but one of my readers emailed me in dismay when a news story appeared about Treasury’s latest market strategy. I’ll use this as an example, but Treasury isn’t the only wine corporation that I could pick on and maybe not even the best example

One element of Treasury’s plan is to develop brands for the “masstige” market segment, which means taking a prestige brand and levergaing it by introducing a cheaper mass market product that rides on the iconic brand’s reputation.

Masstige? Sounds like something from a Dilbert cartoon, which means of course that it is a totally authentic contemporary business term. Prestige fashion house Versace, for example, seems to have developed a masstige product line for mass market retailer H&M. The line was launched in 2011 and I’m not sure where it stands today. Maybe it was a big success? If masstige worked for shoes and dresses, how could it be a bad idea for wine?

I’m sure a prestige association helps sell the cheaper mass market products, but I can think of some examples in the wine business (Paul Masson? Beringer? Mondavi?) where it might have undermined the iconic brand itself a little or a lot, which seems self-defeating. I know that has happened in the fashion field (think about how the Pierre Cardin brand was diluted by cheap logo products) so I imagine it could be a factor in wine, too.

Think Global, Source Global

Here’s another example. Regional identity is more important in wine than in some other industries and Treasury owns some famous “wine of origin” brands — wines associated with particular regions, which are valuable assets. But my worried reader was concerned about Treasury’s plan to source globally to expand the scale of some of these regional brands.

“Building scale via sourcing breadth is one of the most critical platforms necessary for the globalization of wine brands,” according to the report. Gosh, that even sounds like corp-speak, doesn’t it? Logical, I suppose, but maybe locally-defined brands need to be locally sourced to maintain authenticity? Maybe consumers would be suspicious of a Stags Leap wine, to make up an example, that is sourced from Australia or some other distant place as a way of leveraging its brand power? I wonder just how flexible these terroir-based brand concepts are in the real world where consumers are the ones who decide what is authentic and what is bogus.

Global Market Moral Hazard

Some big wine corporations that have had troubles in recent years seem to have made the mistake of thinking that big global markets will soak up all that they (and the other big firms) can produce. It’s a matter of global-think. The global markets are huge. There’s always a market for another dozen containers somewhere in the big world of wine, or so it might seem, and so the risk of failure is misunderestimated, to use a GW Bushism.

In finance we would say that the false sense that the global market is always there to bail you out leads to moral hazard and this is probably true in wine, too. Moral hazard encourages excessive investment and promotes booms and the busts that often follow. What seems to be true for an individual company is not necessarily true for an industry and misunderstanding this sort of risk is downright dangerous in an industry like wine, which is by its nature subject to cycles and booms and busts.

If private- and family-firms avoid the tendency to think global when their markets are local and thus avoid misunderestimating risk and if they really do work to preserve rather than leverage key assets it might help explain their lasting power and influence. Lots of “ifs” there, but its a theory. What do you think?

When I wrote about the global financial crisis in my 2010 book

When I wrote about the global financial crisis in my 2010 book

Thomas Pellechia,

Thomas Pellechia,  The featured essay in the current issue of

The featured essay in the current issue of