We live in a time when problems we face are complicated but many of the answers proposed to address them are very simple. I am suspicious of simple answers to complicated questions, both in general (this was the theme of my 2005 book Globaloney) and when it comes to the American wine industry.

We live in a time when problems we face are complicated but many of the answers proposed to address them are very simple. I am suspicious of simple answers to complicated questions, both in general (this was the theme of my 2005 book Globaloney) and when it comes to the American wine industry.

Draining America’s Wine Lake

Wine Economist readers already know about the American wine industry’s general over-supply problem. Despite several short harvests in a row in California, wine inventories remain very high and prices are falling. As Jeff Bitter pointed out at the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium last month, many thousands of acres of wine grape vines have been removed and more grubbing up is necessary before supply has been downsized to balance with demand. Similar adjustments are taking place throughout the world of wine.

I was interested to learn from Jeff that California’s Central Valley is perhaps closer to equilibrium than, say, the Central Coast. This is in part because growers in the valley can more effectively switch to alternative crops, which cushions the blow of vine removal. Indeed, many large growers already farm multiple types of crops, so the switch is a change of ratio and proportion, not a move into a new line of business.

Some growers would like to “furlough” their vineyards, to pause production until the market has stabilized. But, at least in some areas, this is made difficult because of water use regulations. Water rights can be withdrawn if the land is not actively farmed for several years. So in some areas, where alternative crops are not feasible and water rights are tightly controlled, vineyard removals or furloughs are hard to manage. No wonder there are reports of some vineyards simply abandoned! (I have also heard of one vineyard that was offered at a zero-dollar lease to anyone who would keep production going and, therefore, keep water rights safe.)

Unemployment: Cyclical, Structural, Frictional

The wine market situation is complicated in other ways, too. Both Glenn Proctor and Danny Brager talked about the problem at the Unified in terms of structural versus cyclical adjustments and this got me to thinking about the way economists explain unemployment as the interaction of three forces. I will explain briefly since I think these concepts apply to wine, too.

Cyclical unemployment is caused by cycles in the economy. Workers lose their jobs as firms scale back during a recession, for example, and gain them back (or get other jobs) when economic growth returns. Macroeconomic stimulus (tax cuts, interest rate reductions) are tools of choice to address cyclical unemployment.

Structural unemployment is joblessness due to changes in the essential structure of the economy. Changing patterns of trade, environmental shifts, and technological change are some of the causes of structural unemployment. Some newspaper employees, for example, suffer structural unemployment as demand shifts from physical to digital platforms for information, entertainment, and advertising. One of the concerns about artificial intelligence technology is that it might contribute to structural unemployment.

It is significant that policies designed to address cyclical unemployment such as interest rate cuts will do little to correct (and could even accelerate) structural unemployment problems.

Finally there is frictional unemployment, which is joblessness caused by inefficiencies in the labor market, as happens when there are jobs available in one city and jobless workers in another city, but information inefficiencies, high transaction costs, and other barriers prevent them from productive connection. The current housing market, with higher mortgage interest rates and historically high prices, is one source of frictional unemployment, for example. Job market policies tailored to either address cyclical or structural unemployment problems may have little impact on frictional unemployment. There aren’t many easy answers to complicated questions.

The American Wine Dilemma

These concepts apply to the wine industry in America and other countries today. The wine market has long been subject to medium-term (7- to 10-year) cycles, for example, although “wild card” events such as the COVID pandemic have distorted the pattern. Some wine industry folks have never seen the bottom of the wine cycle before. The fact that the previous “boom” part of the cycle was characterized by a ratchet-up of wine prices (premiumization) makes the down cycle more difficult to predict.

There are also structural changes at work. Demographic transition (baby boomer rise and fall) is part of the situation, but so is the structural shift in attitudes and behavior towards beverage alcohol generally. There also seems to be a structural shift in consumer preferences away from red wines toward white wines. It is hard to predict how and when these structural forces might run their course and when or whether they might reverse.

Finally, there are frictional concerns that take many forms around the world, but here in the United States are perhaps most apparent in wine distribution and retailing. Wine distribution pipelines have narrowed in recent years. I have written that every industry organizes itself around its most important inefficiency (or “bottleneck,” if you know what I mean). Distribution is wine’s bottleneck, not growing grapes or making wine. The fact that this bottleneck has narrowed is significant and could well reshape the industry broadly.

The Age of Uncertainty

If you are looking for a simple answer to the dilemma of American wine, you are not going to find it here. The point, as stated above, is that complicated questions seldom have simple answers. Complexity leads to uncertainty because each of the cyclical, structural, and frictional forces is difficult to predict and their dynamic interaction is sometimes best modeled by chaos theory

So, as I wrote here a few weeks ago, we have entered the Age of Uncertainty. In economics, uncertainty equals risk and risk discourages investment, innovation, and growth. Not what the wine industry needs at this moment. But understanding uncertainty and risk is better than charging ahead in ignorance.

Sue and I recently attended the

Sue and I recently attended the  Always the Age of Uncertainty?

Always the Age of Uncertainty? Galbraith’s Uncertainty Principle

Galbraith’s Uncertainty Principle Everyone knows that the volume of wine sold has declined in recent years, which is a serious problem for many people in the wine value chain. Not every category has suffered equally and there are a few areas of growth. The picture improves a little if we look at the value of wine sold, but this mainly highlights segments where increases in average price have outpaced declining volume.

Everyone knows that the volume of wine sold has declined in recent years, which is a serious problem for many people in the wine value chain. Not every category has suffered equally and there are a few areas of growth. The picture improves a little if we look at the value of wine sold, but this mainly highlights segments where increases in average price have outpaced declining volume. Sue and I have just returned from the 30th edition of the

Sue and I have just returned from the 30th edition of the  The

The  A journalist with a Brazilian newsweekly called me on Thursday to ask for help with a story on China. The magazine is doing a sort of “worst case scenario” report on the potential impact of China’s economic growth on world markets. What would happen to oil prices, for example, if the Chinese used as much fuel per capita as Americans do? Yikes, that would be a lot of drivers using a lot of gas and it would send oil prices through the roof. What would happen if Chinese consumers generated as much waste and pollution per person as people in the West? Once again, the global effects would be dramatic.

A journalist with a Brazilian newsweekly called me on Thursday to ask for help with a story on China. The magazine is doing a sort of “worst case scenario” report on the potential impact of China’s economic growth on world markets. What would happen to oil prices, for example, if the Chinese used as much fuel per capita as Americans do? Yikes, that would be a lot of drivers using a lot of gas and it would send oil prices through the roof. What would happen if Chinese consumers generated as much waste and pollution per person as people in the West? Once again, the global effects would be dramatic. The Brazilians are not the only ones interested in the future of wine.

The Brazilians are not the only ones interested in the future of wine.  I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next?

Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next? As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the

As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the  An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations.

An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations. I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.

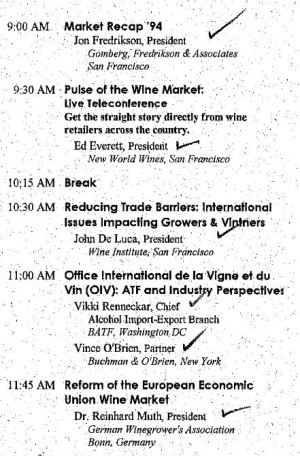

I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.

The economist John Maynard Keynes wrote these words in a 1930 essay called “The Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren” and I have been thinking about them quite a lot recently in the context of the wine industry. Keynes was writing in the depths of the Great Depression. Is wine in (or headed towards) a Great Depression of its own?

The economist John Maynard Keynes wrote these words in a 1930 essay called “The Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren” and I have been thinking about them quite a lot recently in the context of the wine industry. Keynes was writing in the depths of the Great Depression. Is wine in (or headed towards) a Great Depression of its own? I was talking with a group of California winegrowers just before the

I was talking with a group of California winegrowers just before the