Geoffrey Finch, The Hidden Vineyards of Paris (Board and Bench, 2023).

Geoffrey Finch, The Hidden Vineyards of Paris (Board and Bench, 2023).

Urban wineries aren’t surprising anymore. It is not that difficult to truck in grapes and other supplies to make (and then sell) wine in the heart of a busy city. City wineries are not as ubiquitous as local craft breweries, but they aren’t hard to find. If you go to Paris, for example, you’ll find a winery on the first floor of the Eifel Tower.

Urban vineyards are a different matter. Cities, by their very nature, are filled up and built over, with what open land that remains after urbanization devoted to parks, playgrounds, and so forth. A vineyard? That would be a surprise.

But of course, cities have not always looked and operated as they do today. Before the advent of cheap and secure transport, for example, cities had to be much more self-sufficient than they are today. Food could not cheaply and reliably come from far away, so local sourcing was vital. This was especially true for wine in Europe because of its central place in diet, culture, and economy.

You can find remnants of the old vineyards if you look for them. In Venice, for example, the Venissa vineyard is a short vaporetto ride from St Mark’s Square. It’s a different side of Venice, serene like the city itself (La Serrenisima) once was. Sue and I love the vineyard and the hotel and restaurant that the Bisol family has developed.

But wait … there’s more! If you know where to look in Milan you can find the evidence of Leonardo’s personal vineyard reconstructed, according to Professor Scienza, using DNA analysis. Add that to your bucket list!

I was amazed to discover that Paris was once the center of the largest vineyard area in France and the world. This makes sense, however, since the city’s large population required wine, and the local environment was well-suited to grape farming. Parisian vineyards declined slowly and then suddenly, however, due to a number of forces including especially the arrival of the train, which delivered quantities of wines that were better than the local ones (from Burgundy and Bordeaux) or much cheaper (from Langudeoc and eventually Algeria, too).

Parisian vineyards declined but did not entirely disappear. You have to look closely to find them, however, which is what Geoffrey Finch has been doing for over 40 years. His new book is a slim volume packed with insights, information, and colorful illustrations that tell the story of grapes, wine, and Paris.

Finch guides us through vineyards that are used to produce wine, vineyards that don’t yield wine but serve other purposes, and isolated vines too random to be called vineyards but that tell interesting stories. Even the largest of these vineyards is small by the standards of Bordeaux or even Burgundy, but size isn’t the point here. Rather they are a chance to encounter the history of Paris and wine and, if you are lucky, have a taste, too.

We have visited Paris several times, but have never been to Clos Montmartre, the largest vineyards and the only one with commercially available wine. There is even a community wine festival. It’s on our list for the next Paris expedition.

It would be great to visit these vineyards with Finch on one of his tours and to hear his stories in person, but reading The Hidden Vineyards of Paris must be the next best thing because of his distinct sensibility, insatiable curiosity, and obvious fascination with Parisian history. Each vineyard (or individual vine in some cases) has a history that is specific to its subject and also reflective of Paris more generally. Each is a pleasure to read and appreciate.

Taken together, the vineyards and their biographies give a rich sense of what Paris is, has been, and perhaps might be again. The Hidden Vineyards of Paris is informative, entertaining, and well-written. Highly recommended.b

The outline of the

The outline of the  What would a generic marketing campaign for wine look like? I don’t know (I’m not sure

What would a generic marketing campaign for wine look like? I don’t know (I’m not sure I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next?

Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next? It is called a fiasco.

It is called a fiasco. I suppose that the move away from the distinctive fiasco was a bit of an identity crisis for Chianti, but it might not have been the only or most important one as

I suppose that the move away from the distinctive fiasco was a bit of an identity crisis for Chianti, but it might not have been the only or most important one as  The Cecchi family of wine producers invited us to sample their wines and taste the difference and it was an eye-opening experience. The

The Cecchi family of wine producers invited us to sample their wines and taste the difference and it was an eye-opening experience. The As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the

As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the  An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations.

An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations. I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.

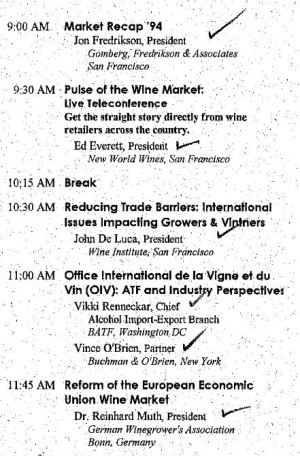

I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.

Rebecca Gibb,

Rebecca Gibb,  Joanne Gibson and Malu Lambert,

Joanne Gibson and Malu Lambert,  Daniel E Bender,

Daniel E Bender,

I didn’t think it was a waste of time because learning about nice wines is almost always a good thing, but I admit I sometimes fall into a less extreme variant of this point of view, favoring native over traditional or international much of the time. But his strong reaction made me think. The vines for this wine had been planted by the winemaker’s grandfather and had helped support three generations of his family. That seems pretty well rooted in terroir, don’t you think?

I didn’t think it was a waste of time because learning about nice wines is almost always a good thing, but I admit I sometimes fall into a less extreme variant of this point of view, favoring native over traditional or international much of the time. But his strong reaction made me think. The vines for this wine had been planted by the winemaker’s grandfather and had helped support three generations of his family. That seems pretty well rooted in terroir, don’t you think? Crisis distillation is back in the news. For those unfamiliar with this wine business term, crisis distillation refers to government programs that buy surplus wine and distill it into industrial alcohol. The point isn’t to increase industrial alcohol supplies but to support prices and incomes in the wine sector by taking excess supply off the market.

Crisis distillation is back in the news. For those unfamiliar with this wine business term, crisis distillation refers to government programs that buy surplus wine and distill it into industrial alcohol. The point isn’t to increase industrial alcohol supplies but to support prices and incomes in the wine sector by taking excess supply off the market.

Sue and I have spent the last two weeks tasting wines from two Michigan wineries,

Sue and I have spent the last two weeks tasting wines from two Michigan wineries, The wines we sampled from Good Harbor Vineyards and Aurora Cellars have roots that go back more than 40 years, which is a very long time in American wine. Founder Bruce Simpson aspired to make good, affordable wines in Michigan and, after studies at UC Davis, he and his wife Debbie established Good Harbor Vineyards in 1980. The operation remains in family hands today and

The wines we sampled from Good Harbor Vineyards and Aurora Cellars have roots that go back more than 40 years, which is a very long time in American wine. Founder Bruce Simpson aspired to make good, affordable wines in Michigan and, after studies at UC Davis, he and his wife Debbie established Good Harbor Vineyards in 1980. The operation remains in family hands today and  Sue and I had an unexpected visitor recently. He said he was an emissary from another world, a place called

Sue and I had an unexpected visitor recently. He said he was an emissary from another world, a place called  Le Cigare Volant — the flying cigar? What kind of a name is that? It is complicated, so I will explain.

Le Cigare Volant — the flying cigar? What kind of a name is that? It is complicated, so I will explain.