How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery.

How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery.

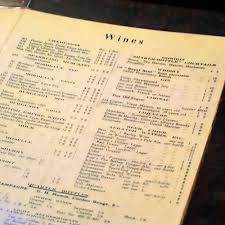

Reading Down the Wine List

Everyone knows that restaurant wine sales are down as the recession has reduced both the number of diners and their willingness to spend a lot of money on wine. One of the best sources of news on restaurant wine sales is the Wine & Spirits magazine annual restaurant issue, which surveys selected wine-friendly restaurants and reports sales trends.

The W&S data give only part of the picture, however, since they tend to survey restaurants with more sophisticated wine-enthusiast customers. What’s happen to wine sales a bit further down the food chain?

Two studies by Ronn Wiegand (publisher and Master of Wine) in the current issue of Restaurant Wine report that US restaurant wine sales were off by 5.5 percent by volume in 2008 while sales of the Top 100 wines fell by just 3.5 percent. This suggests some consolidation in this sector, which will make sense once I tell you what the best selling wines are.

The drop in restaurant wine sales overall is less than the numbers I’ve seen for upscale restaurants. One reason for this discrepancy as I understand it is that Wiegand’s figures come from distributors, who report sales to all restaurants and on-premises establishments, not just purchases by select restaurants. So this gives us a picture of the broader market.

America’s Best Selling Restaurant Wines

Upscale restaurants of the sort that receive Wine Spectator awards get the most attention in the press, but casual dining restaurants are where the volume of wine sales is greatest. The top ten individual wines (by volume not value of sales) in 2008 were (drum roll) …

- Kendall-Jackson Vintner’s Reserve Chardonnay

- Cavit Pinot Grigio

- Beringer White Zinfandel

- Sutter Home White Zin

- Inglenook Chablis

- Ecco Domani Pinot Grigio

- Mezzacorona Pinot Grigio

- Copper Ridge Chardonnay

- Yellow Tail Chardonnay

- Franzia White Zin

None of these is an expensive wine and the #1 K-J is probably the costliest of the lot. The best selling restaurant (“on-premises”) wines are high-volume, widely-distributed inexpensive wines – just the sort that recession-ravaged consumers who want to trade down (in terms of price) and switch over (to a more relaxed view of wine) might find appealing.

Using the rule of thumb that a glass of restaurant wine sells for about the wholesale price of the bottle, these wines would sell from about $5 (for the Sutter Home) to maybe $8 (for the K-J Chard) per glass — and I suspect that a lot of this wine is sold by the glass. An affordable luxury, as they say.

Who Sells the Most Restaurant Wine (and How)?

If you are someone who dines mainly at three star restaurants where the wine list is really a leather-bound book that is handled with biblical reverence (and White Zinfandel must be a typographical error), the facts I’ve just stated about what America drinks when it dines out are probably pretty discouraging. But don’t give up hope just yet.

If you want to see the state of the art in American restaurant wine programs, follow your nose in the direction of the local shopping mall and get in line for a table at Olive Garden. Olive Garden’s 691 restaurants sell more wine than any other restaurant chain in the United States and its sales and education programs are a positive part of the transformation of American wine culture. Olive Garden is the optimistic future of American restaurant wine.

How does Olive Garden, a chain best known for its bottomless salad bowl and endless supply of tasty bread-sticks, sell so much wine (half a million cases in 2006, according to one source, probably much more than that today)? The short answer is education. Americans like wine and enjoy having it with food, but they are intimidated by everything about wine and need education before they are comfortable embracing wine. You’ve gotta learn ’em before you can turn ’em (into mainstream wine consumers).

The educational process at Olive Garden starts with staff, the people who are best placed to influence customer choice. Early on, Olive Garden established a relationship with the family that owns Rocca delle Macie winery in Tuscany. Specially selected staff travel to Italy each year to live, shop, eat, drink, cook and in general soak up knowledge and experience that can be used and shared back home — a nice employee incentive that pays off in higher wine sales.

Back home, in partnership with several California wineries, Olive Garden has established a similar institute in Napa Valley. Many restaurants expect that their wait-staff will pick up wine knowledge – Olive Garden really works at it by providing literally hundreds of thousands of hours of training. Of course, it has the chain-wide scale to make this investment pay off.

Selling Wine By Giving It Away

So Olive Garden staff are likely to know their wine list (37 wines from Italy, California, Washington and Australia, 35 of which are available by the glass) and which wines match well with different dishes, but how to you get patrons to try them – and especially to move out of their comfort zone and try something new?

The answer is … wait for it … to give away free samples! Patrons at many Olive Garden restaurants (this is America — local regulations vary) are offered small samples of different wines along with advice on menu pairing. The Italian house wines are the Pincipato brand made by Cavit that sells for $5.35 a glass and $32 for a 1.5 liter bottle meant to be shared family-style. Bottle prices of other wines range from $21 for the Sutter Home White Zin on up to $110 for Bertani Amarone. Most choices are in the $24-$34 range.

Olive Garden takes the free sample idea seriously, giving away 30,000 cases of wine in 2006 and presumably more today. That’s about 3-4 million tastes, according to my back-of-the envelope calculation. And it’s worth it, both in terms of wine sales and customer satisfaction. Customers like the wine, once they’d had a chance to try it, Olive Garden says, and it helps them enjoy the whole family dining experience more. No argument here — I can see how having one of those 1.5 liter bottles on the table would help a family relax and enjoy their meals.

The Olive Garden website continues the education process for customers who develop an interest, with basic Wine 101 information along with an interactive guide to pairing specific wines with particular menu items.

Confidence Game: Olive Garden, Costco and Trader Joe’s

The Olive Garden system sells wine, obviously, and it sells the idea of wine in a very healthy way. Olive Garden customers are more likely to try new wines and have fun with wine, I think, because they trust the Olive Garden brand.

Olive Garden has obviously invested a lot in its wine program and in research about what will appeal to its customers. There is less perceived risk in trying something new at Olive Garden. This is perhaps especially important in selling some of the Italian wines, where both the producer (Mandra Rossa, for example, or Arancio) and wine name (Fiano or Nero d”Avola) would be unfamiliar to most diners.

In a way, Olive Garden has the same advantage when it comes to selling wine as Trader Joe’s and Costco. The seller’s trusted brand gives buyers confidence in making an otherwise uncertain purchase.

Olive Garden is big enough and smart enough to make the investment required to pursue this wine strategy. It’s a good thing in terms of the development of a healthy American wine culture, but it does contribute to the consolidation of the industry noted at the start of this post. Olive Garden needs large, reliable supplies of each wines to make its system work (minimum quantity 7500 cases, I think), which rules out smaller producers.

But Olive Garden doesn’t have to be everything to everyone and there is plenty of room in the marketplace for other types of restaurants and wine programs. If Olive Garden helps introduce middle America to a healthy idea of wine, it will have done a great service. And I think that’s exactly what’s happening.

Who is the #1 retailer in the wine world? The answer is

Who is the #1 retailer in the wine world? The answer is  Tesco is very focused on innovation and uses its power to achieve it. Tesco has pressed its suppliers to switch from cork closures to screw caps, for example, in order to eliminate the three to five percent loss that is commonly experienced due to TCA cork taint. Anyone who wants to get wines into the Tesco pipe had better not show up with a corkscrew (iconic brands excepted, of course).

Tesco is very focused on innovation and uses its power to achieve it. Tesco has pressed its suppliers to switch from cork closures to screw caps, for example, in order to eliminate the three to five percent loss that is commonly experienced due to TCA cork taint. Anyone who wants to get wines into the Tesco pipe had better not show up with a corkscrew (iconic brands excepted, of course). Our friend Jerry doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would go digging around in the closeout bin or shopping for wine at

Our friend Jerry doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who would go digging around in the closeout bin or shopping for wine at

My last post,

My last post,

How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery.

How an investigation into trends in restaurant wine sales leads to an unexpected discovery. The

The .jpg)