Although it is hard to pick out trends with confidence in the current topsy-turvy wine market environment, it is fair to say that there is growing concern that global wine consumption has reached a plateau. This is not a new phenomenon, as I wrote back in January 2019, when I pointed out “global wine’s lost decade.”

Although it is hard to pick out trends with confidence in the current topsy-turvy wine market environment, it is fair to say that there is growing concern that global wine consumption has reached a plateau. This is not a new phenomenon, as I wrote back in January 2019, when I pointed out “global wine’s lost decade.”

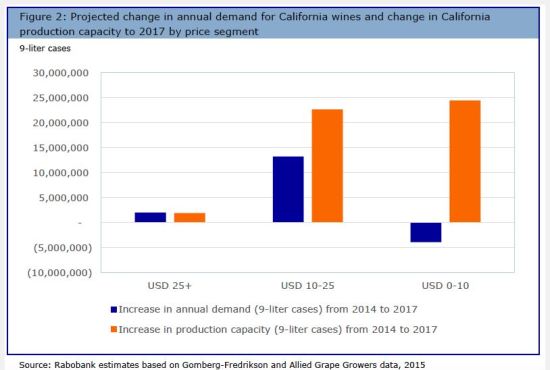

Where do you find growth in a stagnant market? One strategy, which I pointed out in a March 2019 column about Precept Brands success, is to take advantage of the fact that there are always some growing market segments. Flexible producers will follow the money, investing where the growth is. Trying to take market share from other beverage alcohol categories in another strategy, of course, but wine suffers a cost disadvantage here. Wine’s per-serving cost is higher in general that either beer or spirits.

So what is to be done? A recent Rabobank report about global beer provides food for thought about what’s ahead for global wine. Beer? What can wine learn from beer? Well, beer hit a global sales plateau first and so has had more time to develop strategies.

Rabobank’s Beer Quarterly Q3 2021: The Beer Wars analyzes the beer industry’s response to stagnant demand in terms of the different strategies adopted in Japan, the US, and Europe.

Japanese Beer’s Diversification Strategy

The Japanese beer industry faced a crisis earlier than brewers in the US and Europe according to the Rabobank report, and so have had more time to find new growth strategies. Starting in the 1980s the beer market was disrupted by a combination of generational transitions (younger drinkers turned off by what they saw as grandfather’s beer), shifts in path to market (the rise of convenience stores and vending machine sales), and the advent of new competition in the form of chul-hai, an easy-drinking RTD cocktail.

Japanese brewers responded in many ways, including the innovation success of Asahi Super Dry, but the main strategy that the Rabobank report identifies is diversification into other product lines. Japanese brewers compensated for stagnant or falling per-capita beer sales by expanding into other markets from production technology to pharmaceuticals to nutritional supplements where existing strengths could be exploited. The process was slow, the report suggests, and required considerable investment.

It is easy to see wine industry parallels in the problems that Japanese beer faced. Generational transition? Shifting market pathways? Easy-drinking alternatives (think hard seltzer today). Constellation Brands has diversified within the beverage alcohol space through its Mexican beer business and made initial moves into cannabis, too. LVMH has long pursued a diversification strategy — its wine business is part of a diversified portfolio of luxury brands.

US Beer Follows the Money

A second strategy, which the Rabobank report associates with the US beer market, is diversification into other beverage categories such as ready-to-drink coffee and tea, energy drinks, sports drinks, hard seltzer, and so forth. Part of the logic, I think, is to exploit scale economies in beverage distribution and the name recognition derived from established brands and part is simply following market growth wherever it takes you. MolsonCoors changed its name to MolsonCoors Beverage to signal that it isn’t just a beer company any more.

I admit that I was stunned to see Pabst Blue Ribbon hard coffee on beer aisle of the local Safeway, but it fits with this strategy and reminds me of the time a few years ago when Coca Cola decided that it could leverage its distribution network comparative advantage to enter the wine business by purchasing Taylors wine company (transforming it into Taylors California Cellars) as well as Napa Valley’s Sterling Vineyards. Coca Cola lost interest in their wine diversification strategy after a few years, however, as the margins on wine couldn’t match its soft drink profits and sold the brans to Seagrams.

It is easy to see some wine producers adopting this strategy in the US, too, especially in the canned segment where wine, various wine spritz drinks, and hard seltzer products fill the shelves.

European Beer M&A and Internationalization

Finally, the Rabobank report identifies an M&A and internationalization strategy that it associated with European beer producers. This is the “go big” part of “go big or go home.” European brewers such as Heineken and Carlsberg have evolved into firms with both multinational markets and multinational production networks, too.

Heineken is currently negotiating purchase of control of South Africa’s Distell, the world’s second largest (after Heineken itself) cider maker as well as an important spirits and wine producer. This transaction would further expand Heineken’s footprint in Africa, a market with substantial potential for growth.

Consolidation has been an important recent theme in the wine business, too. Gallo’s scale after the Constellation Brands deal is quite incredible. And I think this trend will continue both in wine production and distribution. But the global wine is still quite fragmented compared with global beer.

What Can Wine Learn?

Beer has had to face a stagnant global market for longer than wine and has developed a number of strategies to expand volume or grow margins. Very large wine companies have learned the lessons of their beer industry colleagues and pursued similar approaches, but it is still early days for wine compared to beer.

Can beer provide insights for medium sized wine producers, of which there are many around the world? This is less clear simply because consolidation in the beer industry has hollowed out this market segment

“Can U.S. Wine Win Back Its Mojo?”

“Can U.S. Wine Win Back Its Mojo?”

“It was the best of wines, it was the worst of wines (apologies to fans of Charles Dickens). The global wine glass seems both quite empty and full to the brim.”

“It was the best of wines, it was the worst of wines (apologies to fans of Charles Dickens). The global wine glass seems both quite empty and full to the brim.”

My copy of the second edition of Michael Cooper’s

My copy of the second edition of Michael Cooper’s .jpg)