Sue and I returned from our visit to South Africa with many strong impressions and great memories. Maybe the single thing that struck us the most is this: the Cape Winelands are a wonderful wine tourism destination. The best we have ever visited? Perhaps!

Sue and I returned from our visit to South Africa with many strong impressions and great memories. Maybe the single thing that struck us the most is this: the Cape Winelands are a wonderful wine tourism destination. The best we have ever visited? Perhaps!

And this is important because wine tourism is now widely seen as playing a critical role in the industry. It is not just a way to sell wine at the cellar door (with direct sales margins), although that can be important to the bottom line. And it is not just a way to fill hotel beds and restaurant tables, although that is clearly important from an economic development standpoint.

A Sophisticated Industry

Wine tourists are also wine ambassadors, who carry a positive message back home with them. They sell the place, the people, the food, and of course the wine. That’s why Australia is betting so heavily on wine and food tourism to turn around its image on international markets. My friend Dave Jefferson of Silkbush Mountain Vineyards has recently called for more attention to promoting wine tourism in South Africa and I think he’s on the right track.

The South African wine tourism industry is very sophisticated as you might expect with people like Ken Forrester and Kevin Arnold involved. Forrester has made his restaurant 96 Winery Road a key element in his winery’s business plan and Arnold says that he sees filling hotel beds as a primary objective. If the hotels are full of wine tourists, he is justifiably confident that his Waterford Winery will get its share of the business. They are two of a growing list of South African wine producers who have invested in the wine tourism strategy.

The variety of wine tourism experiences is striking ranging from vineyard safaris at Waterford to a stately home visit at Antonij Rupert to luxurious spa facilities at Spier. We loved the lush gardens at Van Loveren in Robertson and the warm Klein Karoo feeling at Joubert-Tradauw in Barrydale. The opportunity to sip Riesling during a children’s theater performance in the forest at the Paul Cluver Estate in Elgin was memorable. There is always something new around the corner.

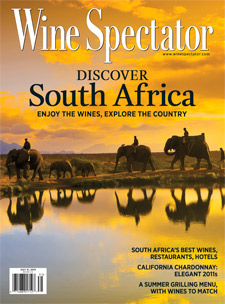

Our photo collection from this trip seems to have an equal number of images of beautiful scenery and mouth-watering plates of food. I think wine tourists will be struck both by the physical beauty of the Cape Winelands and by the high quality restaurants that a great many of the wineries feature.

A Sticky Experience

The splendid winery restaurant opportunities in South Africa may come as a shock to many Americans who are used to touring at home since in the U.S. the rule seems to be that food and wine should not mix – at least not at wineries. That’s wrong, of course, but the result of America’s archaic alcohol regulations.

I think the restaurant at Domaine Chandon may be the only one of its kind in Napa Valley, for example. And of course in some states including New York wine sales in supermarket settings are forbidden. Wine and food — a dangerous combination!

One key element of the wine tourist business is to create an experience that makes visitors slow down, stop and take a a little time to let the impressions sink in – a “sticky” experience if you know what I mean. Vineyard and winery tours can do this and various sorts of specialized tasting and pairings experiences work, too, but maybe nothing is quite as effective as the opportunity have a great meal in a fabulous setting along with the wine you have just sampled.

The list of great winery restaurants in South Africa is very long – some of the highlights from our brief visit are Jordan (where Sue enjoyed the beet salad above), Diemersdal, Stark-Condé, Lanzerac, Glen Carlou, La Motte, Kleine Zalze, Fairview and Durbanville Hills (the view shown in the photo at the top of the page is of Cape Town and Table Mountain at sunset as seen from the Durbanville Hills restaurant).

So what are the keys to being a wine tourist in South Africa? Well, first you have to get there, of course, and I think many people wish that there were more direct flights to Cape Town. Our SEA-LHR-CPT route on British Airways was long and tedious as you might imagine, but pleasant and efficient by contemporary air travel standards.

Wine Tourist Checklist

Once you are on the ground, will need a couple of essentials. Here is my short list.

First, a rental car with a GPS unit. You can do a little wine touring without a car, of course, booking one of the many day tours out of Cape Town. The historic Groot Constantia winery is actually on one of the routes of the hop-on hop-off tourist bus that shuttles visitors to all the main scenic location. But renting a car opens many more doors. The roads in the Cape wine region are mainly quite good and and the region itself is fairly compact, so driving is certainly an attractive option.

South Africa drives on the same side of the road as Britain and Australia but the adjustment if you have to make it is relatively easy. You will need the GPS because many of the wineries are a bit off the beaten path and while GPS units all have their quirks, they are extremely useful here.

Second, buy a Platter’s Guide as soon as you hit the ground in Cape Town. You can get a physical copy or a digital subscription, but be sure to get a Platter’s Guide. Most people will buy this guide for its ratings and recommendations of the current release wines of just about every South African producer, which we found very helpful even if subjective ratings need to be used with care. But the wine ratings are not the whole story.

I especially like Platter’s for its detailed factual information about each winery, which I see as a necessary prelude to a successful visit — plus the practical contact and visit details, including GPS coordinates. Many wineries are on unnamed roads, so it is necessary to have the latitude and longitude coordinates and Platter’s data is very up to date.

These resources, plus a sense of adventure and a curious nature, are the essential equipment for a successful South African wine tourist trip (common sense helps too — as the sign at Groot Constantia says, don’t feed the baboons!).

If you would like to go beyond the basics, I heartily recommend Tim James’s excellent 2013 book Wines of the New South Africa, which provides more depth and detail concerning the history of South Africa wines, the grape varieties, the regions and many of the wineries. I studied this book before our trip and the effort paid off.

I love maps, but I could not find a wine atlas of South Africa here in the U.S. As we were leaving the Cape area Cobus Joubert gave us a lovely Cape Winelands wall map that he has produced and I wish I knew about it before we came. It is an impressive and beautiful document with a map of the wine regions on one side and basic information about the wineries (including those critical GPS coordinates) on the other. Not essential, I suppose, but very useful and very desirable and it is a great addition to my collection.

What if you can’t travel to South Africa? Then I guess they have to get their wines to you. I’ll talk about the new wave of export plans that will make South African wines more widely available in the U.S. market next week.

>>><<<

I am known to love the braai, South Africa’s national feast. Meat grilled over wood coals, salads and veggies, wine and friends. Can’t beat it. Nothing brings South Africans together like a braai.

I am known to love the braai, South Africa’s national feast. Meat grilled over wood coals, salads and veggies, wine and friends. Can’t beat it. Nothing brings South Africans together like a braai.

Special thanks to Albert and Martin at Durbanville Hills, Meyer at Joubert-Tradauw and Johann at Kanonkop for inviting us to join their braais!

President Obama’s recent trip to Africa (including his much publicized pilgrimage to South Africa) presents us with a good opportunity to reassess our views. Africa has its problems and challenges (don’t we all!), but also successes and opportunities. This is true generally and, thinking specifically of South Africa, about wine.

President Obama’s recent trip to Africa (including his much publicized pilgrimage to South Africa) presents us with a good opportunity to reassess our views. Africa has its problems and challenges (don’t we all!), but also successes and opportunities. This is true generally and, thinking specifically of South Africa, about wine.

Durbanville Hills was founded in 1999 as a partnership between Distell and seven wine farms in this region and the first wines were released in 2001. This area has a long history of wine growing — the youngest of the farms was founded in 1714 according to the winery website.

Durbanville Hills was founded in 1999 as a partnership between Distell and seven wine farms in this region and the first wines were released in 2001. This area has a long history of wine growing — the youngest of the farms was founded in 1714 according to the winery website.

My recent post about

My recent post about