The world is awash with wine, or so it seems from reading the news. Down in Australia, they are counting up the gallons of unsold wine in a new (to me) measure: number of Olympic-size swimming pools full. Rabobank estimates that the surplus would fill 859 big pools or, if you want a more conventional measure, about 2.8 billion bottles. That’s a lot of surplus wine.

In France, the government has allocated two hundred million euro for crisis distillation. Surplus wine will be bought up to support local prices, and then distilled into industrial alcohol. The next time you use alcohol-based hand sanitizer at your favorite Paris restaurant it might be based on wines from Bordeaux or the Rhone.

Rioja is swimming in wine, too, and here in the United States, there are big stocks of bulk wine for sale in California and thousands of acres of surplus vineyards in Washington state.

This Time is Different

Surplus wine is not a new thing. Wine is an agricultural product and so it is prone to the famous “cobweb” market theory that predicts periodic booms and busts. Turrentine, the California wine and grape brokerage, has cleverly adapted this idea to the wine sector with their “Wine Business Wheel of Fortune.” But this kind of surplus is relatively short term and what we see in the market today looks more permanent.

Sometimes government policies create wine gluts. This is a big part of Australia’s problem today, of course, as Chinese foreign policy has essentially cut off Australian wine from its biggest export market for several years. And the European Union’s famous “Wine Lake” was filled up by price support policies that encouraged over-production to stabilize producer incomes.

If wine surplus is not unusual, what is different about this time? Surpluses today are global not just national. And the driving force is primarily insufficient demand, not excess supply. Something’s changed to create a new global wine environment. What happened? It is a complicated situation, but I’ll try to scratch the surface in a helpful way today and in next week’s Wine Economist.

The Global Wine Glut in Perspective

The graph above (taken from the most recent OIV global wine market report) shows the volume of global wine consumption since 2000. Wine consumption rose steadily for the 20 years that ended with the global financial crisis in about 2007. This was the golden age of wine with many producers (think Argentina and New Zealand) entering global markets with great success and worldwide wine consumption on the rise.

The pause during the financial crisis was thought at the time to be a temporary phenomenon, but in retrospect, we can see that it was the start of what I have called “wine’s lost decade” with stagnant wine sales. The years of steady growth were no more.

Wine consumption fell during the COVID-19 pandemic period, but we expected it to bounce back when the health crisis passed. It hasn’t and in fact, global consumption has fallen back recently to levels not seen since the early 2000s. The picture looks different if we measure the value of sales not the volume of purchases because of the premiumization trend. But people are drinking less wine and less wine than we are growing.

Is there a general theory to explain what happened to global wine? There are lots of special theories that, in an ad hoc sort of way, try to explain individual circumstances. I’ve identified three general theories that help me think about this situation. I’ll analyze two of them briefly below, saving the third for next week’s Wine Economist.

Theory 1: The Generation Gap Hypothesis

The Generation Gap Hypothesis is much discussed here in the United States. The Baby Boom generation powered that long rise in wine consumption, the theory holds, but the following generations failed, for one reason or another, to engage with wine with the same ardor as their parents and grandparents. Total demand cannot be sustained because younger drinkers have not increased consumption to replace the falling demand by boomers as they age.

The younger audience is just different, in this telling, and the task ahead is to introduce them to wine’s appeal through marketing or perhaps cultural education programs. In many wine countries, affiliates of an organization called Wine in Moderation are active to present the positive case for wine in opposition to prohibitionist forces.

It is difficult to organize a response to the Generation Gap problem because generic marketing programs are costly and not always effective (and wine producers and regions have strong incentives to invest in private promotion as opposed to generic programs).

The assumption that generations are fundamentally different leads to the uncomfortable question: Which generation is the anomaly? Are Boomers the norm and the problem is to get Millennials and others to get in line with them? Or, in fact, are Boomers a special case? Was that long wine boom the result of special circumstances? If so, how likely are those circumstances to reappear? Tough questions.

I think generational analysis is very useful in understanding the global wine glut, but it is important to be careful in drawing conclusions. I remember a university colleague of mine who cautioned his Asian Studies student to avoid popular “Asian Values” explanations of political and economic conditions in Japan, Korea, Singapore, etc. “Asian Values” can be twisted to explain anything that might happen, he told his students, so it isn’t valid on its own. Economic events ought to have economic explanations, too, and ditto political events. That’s how I see the Generation Gap hypothesis.

Theory 2: The Life Cycle Hypothesis

The Life Cycle Hypothesis presents a very different theory of the global wine glut. The hypothesis holds that generations are more alike than different in many ways. In particular, the demand for wine remains latent until consumers reach a certain stage in their lives. Millennials are just now approaching this stage and later generations are still in the queue. Wait for it, as Radar used to say on M*A*S*H, and they will discover wine.

This sounds like good news, but it really isn’t because post-Boomer generations are smaller and so, even if and when they find wine, there won’t be enough of them to replace Baby Boomer consumption levels. No use waiting for wine consumption to surge (and not much use in generic promotion, etc.). Supply adjustments are necessary and the sooner the better.

One question that the Life Cycle Hypothesis raises is why the big boom in wine sales only happened when the Baby Boomers came of age. Why didn’t previous generations get the wine bug before them? An answer is, of course, that Boomers represent a surge in the population curve, so anything they do has had a bigger effect, and the generations that immediately preceded them might have understandably had their normal cycle patterns interrupted by the Great Depression and World War II. So maybe the cycles will repeat as this hypothesis suggests, smaller than the Boomers but otherwise much the same.

An Economic Theory?

I find both hypotheses useful in understanding the global wine glut, but my Asian Studies colleague’s voice haunts me. I would be more satisfied if there were an economic theory to explain the economic fact of wine’s over-supply.

Come back next week for my attempt to provide an economic theory of the global wine glut.

>><<<

A book that I have found useful in thinking about generational analysis is The Generation Myth: Why when you’re born matters less than you think by King’s College London professor Bobby Duffy. Generations matter in Duffy’s analysis, but only when taken in context. Food for thought.

Crisis distillation is back in the news. For those unfamiliar with this wine business term, crisis distillation refers to government programs that buy surplus wine and distill it into industrial alcohol. The point isn’t to increase industrial alcohol supplies but to support prices and incomes in the wine sector by taking excess supply off the market.

Crisis distillation is back in the news. For those unfamiliar with this wine business term, crisis distillation refers to government programs that buy surplus wine and distill it into industrial alcohol. The point isn’t to increase industrial alcohol supplies but to support prices and incomes in the wine sector by taking excess supply off the market.

Everyone knows that the volume of wine sold has declined in recent years, which is a serious problem for many people in the wine value chain. Not every category has suffered equally and there are a few areas of growth. The picture improves a little if we look at the value of wine sold, but this mainly highlights segments where increases in average price have outpaced declining volume.

Everyone knows that the volume of wine sold has declined in recent years, which is a serious problem for many people in the wine value chain. Not every category has suffered equally and there are a few areas of growth. The picture improves a little if we look at the value of wine sold, but this mainly highlights segments where increases in average price have outpaced declining volume. I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

I have been thinking a lot recently about how much things have changed since the 1990s and what the future might look like in this light. The event that has provoked this unexpected thoughtfulness is the upcoming

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it

One of the forces that powered economic globalization was the collapse of Communism, which opened up a world of trading and investment opportunities. We called it Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next?

Not everyone was convinced that the new history was valid. My favorite scene was where Robinson poured a glass of New World Pinot Noir and asked a famous Burgundy producer what she thought. The winemaker scowled at her glass and proclaimed that Oregon shouldn’t make something like this. They should find their own terroir, she said, invoking that mystical French phrase almost like a curse. Oregon on the same stage as Burgundy? It’s like the end of history. What next? As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the

As harvest 2023 draws to a close, many of us are gearing up for the 2024 edition of the  An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations.

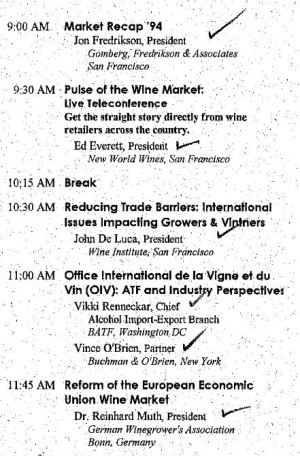

An insightful forecast! But the situation today is pretty much the mirror image of that report. Demographic trends are widely seen to work against wine and alcoholic beverages generally today. Some consumers are wealthier but don’t necessarily feel that way because of pressure from inflation, rising interest rates, higher housing costs, and other factors such as student loan obligations. I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.

I have been involved with the Unified since 2012, mainly as moderator and/or speaker at the Wednesday morning State of the Industry session, the largest gathering of a three-day event. So I was interested to see what the equivalent program looked like at Unified I.